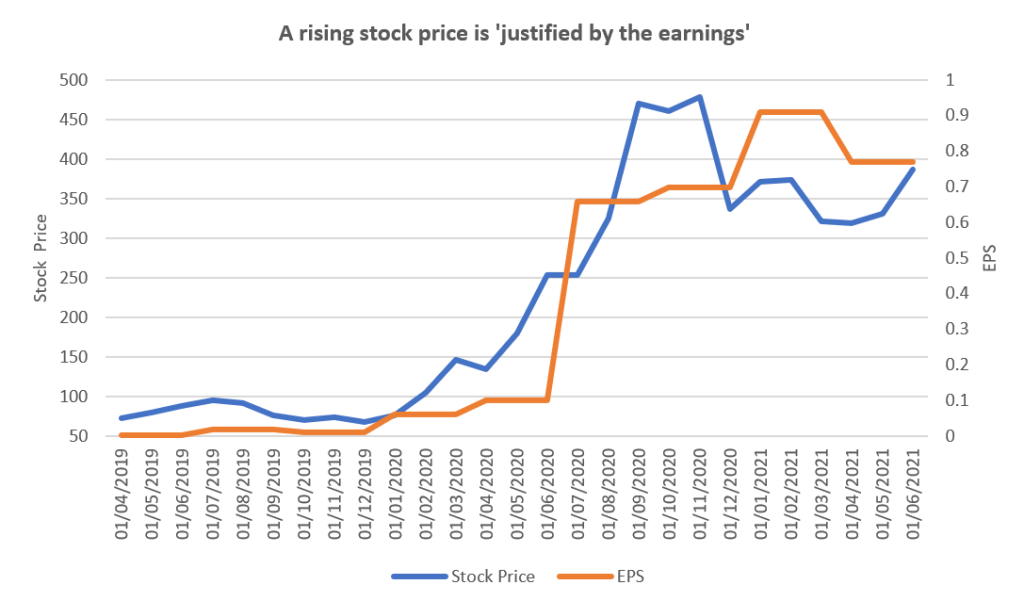

When a stock price has been enjoying a strong spell of performance it is increasingly common to see people argue that the move is ‘justified’ because earnings have been growing alongside it. The statement is usually accompanied by a chart a little something like this:

The point typically being made is that the company in question is not expensive because its increasing stock price is simply a reflection of improving fundamentals. This is a very simple and appealing notion, and also one which plays incredibly well visually. The problem is it can be exceptionally misleading as it ignores the critical variables that most long-term equity investors should care about.

Passing over the dual axis skulduggery which is so often apparent when these types of charts are presented, there are two major issues with making claims about the relationship between stock price performance and earnings growth:

1) Mixing the past with the future: EPS numbers are a reflection of the historic earnings of a company, while a stock price should (in theory) be based on expectations about the future earnings potential of a company. The only way that movements in EPS can ‘justify’ a current stock price is if it somehow affords us supreme confidence in the ongoing earnings prospects of that business. It may tell us a little, but it certainly does not give us a good answer to seemingly vital questions such as – how cyclical are the earnings of the business? What structural pressures might come to weigh on future profitability?

2) Ignoring valuations: The other glaring issue with such claims is that they seem to entirely ignore the valuation of the company in question. I appreciate that value has become a somewhat arcane topic but the earnings growth of a business surely has to be considered relative to its valuation. If we are attempting to assess the extent to which the EPS trajectory of a business is fairly reflected in its stock price movements, whether that business is valued on 5x earnings or 50x earnings feels like an important piece of information, but one which is often disregarded.

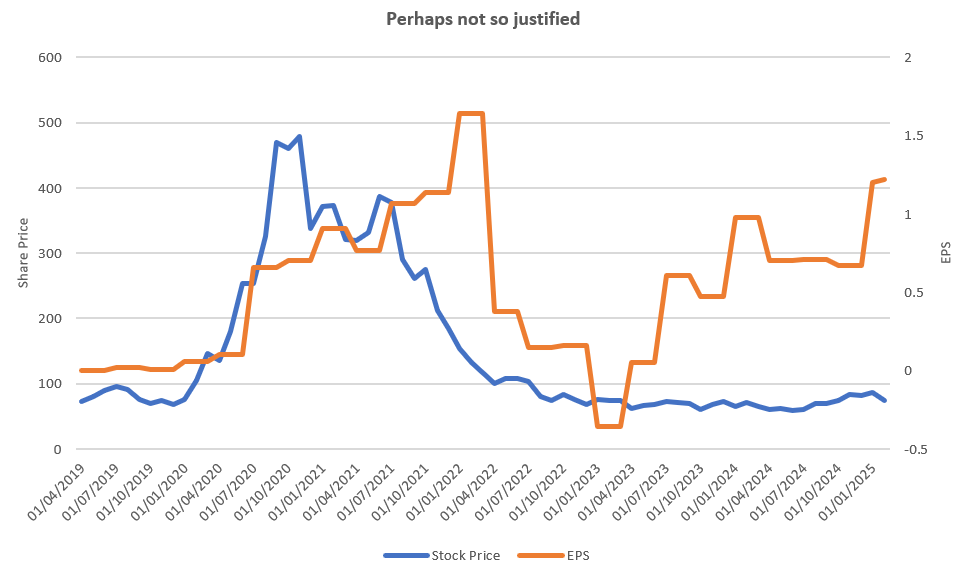

For a stock price to be fundamentally ‘justified’ in any way, we need to have a view on the valuation of a business relative to its future profitability. Observing a rising stock price and improving EPS really doesn’t help us answer such questions as much as many people seem to assume. Stock price moves can be justified by EPS moves, until they aren’t:

Although this type of comparison might not give us a great deal of information about the worth of a company, it does tell us a lot about the behaviour of investors and corporate management:

It’s all about earnings momentum: I have met many, many active equity investors in my career and I would say the most common approach is one based on earnings momentum; where the aim is to identify companies that are enjoying improving and consistently upgraded EPS. This is often not what is stated in their investment philosophy, but very apparent in their behaviour (there is a stigma attached to momentum investing and, unless you are a quant, nobody likes to admit they do it). The stock price to EPS chart is a simple representation of this type of momentum-driven activity.

This ubiquity of this type of investment approach is self-perpetuating. The more investors react to short-term earnings, the more stock prices react to short-term earnings and further encourage the behaviour. It is also a rational approach for many investors to adopt – if you have a time horizon of one or three years, then taking a momentum-orientated approach is likely the best survival strategy. Although you might care about the valuation of a business, by the time it starts to matter you may well be caring without a job.

Such momentum-led investors are as much, if not more, focused on how other investors will react to fundamental developments in the business, rather than the intrinsic merits of those developments to the business itself. There is nothing inherently wrong with such an approach, it is just different to being concerned about a company’s long-term value.

Corporate myopia: One of the consequences of the preponderance of momentum-orientated investors focused on short-term earnings developments is in executive behaviour. If positive stock price moves are increasingly the result of near-term EPS performance this will inevitably alter the decision making of management (on the assumption that their incentives are aligned with how the stock price performs). It seems reasonable to believe that there will be many occasions when a decision made with the objective of maximising short-term stock price performance is very different to one where the objective is long-term shareholder value maximisation. It would be nice if they were the same, but I seriously doubt they are.

The more short-term investors are, the more short-term management are. And so the cycle continues

The stock price of a company rising alongside its earnings really doesn’t help us understand whether it is justified or not, nor does it give us much indication about the long-term value of a business. Rather such comparisons tell us more about the type of investor we are.

* Charts comparing long-run equity market performance with earnings growth are fine. We should expect these to be closely related over time.

** To my mind, there are three types of active investors: Momentum, value and noise. Momentum investors care about price and are shorter-term. Value investors care about valuation and are longer term. Noise investors do random stuff and create opportunities for value and momentum investors.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).