Until recently I was seemingly one of the few people who hadn’t seen the TV show ‘The Traitors’. It became popular so quickly that my stubborn, contrarian streak prevented me from indulging. After some persistent persuasion from my children, however, I succumbed and have been watching the latest UK ‘celebrity’ version. Not only do I have to reluctantly admit to enjoying it, but I have found the contestants’ – often baffling – approach to the game starkly reminiscent of some of the most destructive investor behaviours.

For the uninitiated, the game is very simple. A group of (20 or so) people are put together and a small subset (usually 3) of them are secretly selected to be ‘traitors’. Each day the traitors covertly select one of the ‘faithfuls’ to ‘murder’ (remove from the game). Also, each day, the entire group have to discuss and vote to banish a member of the group who they suspect of being a traitor. For the faithfuls the aim is to rid the group of traitors, while for the traitors it is to remain undetected until the end and claim a prize for themselves. (Party game fans may recognise this structure from Mafia / Werewolf).

A distinctive feature of the game is the almost complete absence of useful evidence the players can use to guess who might be a traitor in the group. The traitors are selected by the producers prior to the show, and players must make judgements based on their interactions with each other during the game.

The way players decide on who to banish for being a suspected traitor follows a consistent blueprint:

– There is virtually no meaningful evidence about who is a traitor.

– All players significantly overstate their skill in ‘reading’ people and hugely overweight meaningless information.

– Players construct persuasive, compelling and entirely spurious reasons about why another participant is a traitor.

– The players who put together the most elaborate arguments are considered smart even though they are consistently wrong.

– The player identified as a traitor is banished and it transpires that they were a faithful.

– Players lament their approach and consider whether a different strategy might be worth considering next time.

– In the following round they do precisely the same thing, seemingly forgetting it didn’t work before.

These are all very human behaviours and almost identical to those that we see from investors attempting to predict the short-term movements of financial markets.

The hallmarks of which are:

– An environment defined by noise and very few signals.

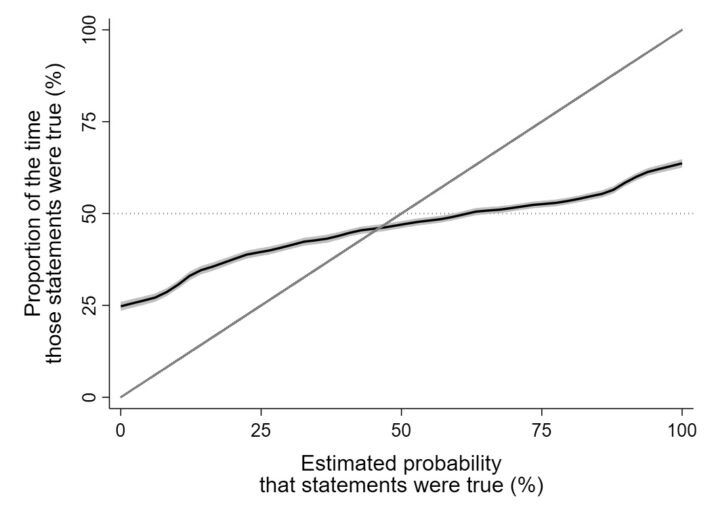

– Massive levels of individual overconfidence in the skill to make predictions about asset class performance.

– A wonderful ability to create impressive and coherent stories about market conditions.

– Credibility and airtime given to investors who sound smart.

– Those investors frequently being wrong.

– Everyone carrying on doing the same thing anyway without acknowledging it didn’t work before.

—

Whether we are trying to guess who the traitor is in a party game or predict the performance of US equities over the next 6 months, the patterns will be familiar. We will inevitably see evidence where there is none, be wildly overoptimistic about our own capabilities, and create stories to alleviate the discomfort of randomness and uncertainty.

Human behaviour doesn’t change much, just the context.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

All opinions are my own, not that of my employer or anybody else. I am often wrong, and my future self will disagree with my present self at some point. Not investment advice.