You are running a multi-asset portfolio and know for certain that over the next five years there is a 20% chance of an occurrence that will cause it to suffer severe losses. Fortunately, there are some assets that you could add to the portfolio that would protect it from most of the drawdown – but there is a catch. Investing in these defensive positions will cause the portfolio to meaningfully but not disastrously underperform its benchmark in the other 80% of future scenarios. What is a rational investor to do?

It depends.

If we are investing for ourselves, we would almost certainly buy the assets that provide some insurance – the risk of underperforming a benchmark is largely irrelevant. What we care about is meeting our long run objectives.

But what if we are running a portfolio where relative returns matter? What if poor relative returns might cost us our job? The incentives change quite dramatically here – what is rational for an individual investor might not be so rational for a professional portfolio manager.

What is worse: a 20% chance of severe losses, or an 80% chance of underperforming for five years? Five years is a long time. Most investors have patience for about three years of sub-par returns.

The primary goal of running a diversified, long-term portfolio should be to maximise the probability of delivering good enough outcomes, while minimising the likelihood of very bad results. It requires us to make decisions about things that could happen but don’t. This seems obvious but the structure of the industry makes it far from easy to follow.

In the (admittedly heavily stylised) example I outlined a professional investor who makes the smart decision to protect the portfolio from a low but meaningful probability risk looks like they are doing a bad job in 80% of future worlds. Conversely, the investor focused on improving the odds of personal survival looks like they have made better choices 80% of the time.

The underlying challenge is that good portfolio management is about creating a mix of assets that is robust to a complex and chaotic world, whereas our means of measuring and incentivising success assumes the world is linear. A choice was made and it was either right or wrong.

This situation creates an agency problem where a portfolio manager is primarily assessed on an outcome that is subordinate to what should be their primary goal, and this can overwhelm their decision making (whether they admit it or not).

If the ultimate aim of a portfolio is to deliver a real return of some level over the long-run, but the portfolio manager has a separate reference point (benchmark or peer group) and time horizon (three years if exceptionally lucky, probably much shorter) their choices will almost inevitably be driven by the latter. That might be entirely acceptable, but we should not ignore that it will encourage very different behaviours.

Of course, having these types of discussions is like howling into the void – nobody really cares. In no other industry is Goodhart’s law (when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure) more apparent than the investment industry. You could boil the whole thing down to one dictum: “number higher good, number lower bad”.

Doing anything other than obsessing over short-run relative portfolio performance is admittedly exceptionally messy. Nobody is going to wait twenty years to find out if something has worked well, and you can excuse any investment mistake by saying: “I was just preparing for a world that didn’t occur”. Just because something is imperfect and difficult, however, doesn’t mean it is not better than the alternatives.

What has seemingly been forgotten is that there is a yawning gulf between these two statements:

“I am investing to meet my clients’ long-term outcomes, hopefully my approach will mean I can do it better than others over time.”

and

“I am investing to beat the returns of people doing similar things to me, hopefully I might also deliver good long-term outcomes”.

The focus of these two statements is completely distinct and the types of decisions we are likely to make similarly disparate.

Although the investment industry is not going to change, it is worth asking whether a portfolio manager’s incentives are skewed so much that decisions that are good for them might not be best for their client.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Uncategorized

Thinking the Unthinkable (About US Assets)

Back in December, I wrote a piece expressing concerns about the ubiquity and strength of the “US exceptionalism” narrative. A heady mix of overconfidence in our ability to predict an always-uncertain world, stellar past performance, and expensive valuations is always a reason to worry. At the time, the overwhelming consensus was that the US economy and stock market could only ever outperform others. Writing that piece felt a little heretical. Four months later, it feels uncontroversial. Why did everything change so quickly — and what does it mean for investors?

We Ignore Risks Until We Feel Them and See Them

The problem with the US exceptionalism argument was not that it was without any merit, but that investors became wildly overconfident that it was undoubtedly true. That belief — reflected in extreme valuations and returns — became far too strong. US outperformance wasn’t seen as merely likely; it was inevitable.

When something persists for a long time — such as the dominance of US assets — it becomes difficult (perhaps impossible) to imagine any other outcome. What has changed in recent months is that investors have begun to acknowledge a broader range of possible futures. Risks to the US are now being taken seriously when previously they were ignored.

The World Is Not More Uncertain — But We Are

I’m always sceptical when investors say the world is now “more uncertain.” Was it really more certain before it became uncertain? What people mean is that they are now assigning meaningful probabilities to a wider array of plausible scenarios. The future is not more uncertain — we are just being more realistic about it.

Overconfidence and Complacency Create Fragility

Why has sentiment changed so quickly? Because when investors are complacent about risks and overconfident about the future it creates fragile systems. When we behave as if one outcome is certain, we are — by definition — unprepared for anything else. We cannot be resilient to scenarios we have entirely discounted.

Most Major Investment Errors Involve Mistaking the Cyclical for the Secular

One of the most consequential mistakes investors make is treating cyclical phenomena as if they are permanent. The peak of any asset performance cycle usually coincides with vehement arguments that the trend is not temporary. High valuations and significant capital flows at these moments reflect the belief that nothing will change. The longer the upswing lasts, the stronger the secular argument becomes.

Incentives Drag Us Away from Sensible Investment Disciplines

A substantial portion of the inflow into US assets over the past decade has come from investors making prudent decisions to hold meaningful exposure to the world’s largest economy and stock market. However, another significant portion was driven by performance-chasing. The pain — and perceived risk— of poor relative returns from holding non-US assets forced many investors’ hands.

For non-US investors, allocating to US assets made sense when they were performing well. What they are now realising is that ‘improved global diversification’ can easily morph into concentrated exposure to a single country when sentiment turns.

Non-US Investors Had It Too Good

Non-US investors who adopted a global approach have enjoyed remarkable returns — exposure not only to a dominant stock market but also to a strong US dollar, which has also acted as a safe haven during market stress. That’s an ideal combination. But it’s also an extraordinary one — and not something we should expect to continue indefinitely.

We shouldn’t doubt this dynamic persisting because we can predict the future, but because betting that it will continue is inherently risky. Investors are used to pricing in the political risks of China or the stagnation in Europe. But many hadn’t considered the possibility of a world where US equities and the dollar are weak simultaneously — simply because it hasn’t happened for so long. They should consider it now — not because it will happen, but because it could.

Nobody Knows What Happens Next

Most people were wrong about the inviolable nature of US exceptionalism and wrong about the consequences of Trump’s election victory, so don’t listen to anyone who claims to know what comes next. The speed with which we’ve shifted from “ongoing US dominance” to the “decline of the US empire” tells us all we need to know about market predictions — and those who make them.

What Should Investors Do?

There’s a real danger that investors overreact to the current market environment. The shock of risks materialising — risks they had previously ignored — may tempt them into drastic shifts in their investment approach. That would likely be a mistake. Swinging from “no risk in US assets” to US assets becoming “exceptionally high risk” is unlikely to produce rational decisions. The truth lies somewhere in-between.

Investors should use this relatively limited reversal in US performance as a moment to reflect: Has the extraordinary performance of US assets made them complacent about risks they now feel significantly exposed to?

The Critical Question for Investors

Many investors will now devote time to forecasting the effects of shifting political and economic dynamics on US assets. This is the wrong approach. It’s always difficult, but right now it’s impossible. We must resist this temptation or face making a succession of inescapably poor choices.

Instead, investors should be asking this:

Have I made long-term, structural investment decisions that were overly influenced by a prolonged period of US outperformance — leaving me vulnerable to a changing environment?

This might apply to non-US investors who’ve gone all-in on US assets, assuming the past fifteen years will repeat forever. Or US-based investors who see international diversification as pointless because “the US always outperforms”. In other words:

Have portfolios been optimised based on an unusually favourable, possibly unrepeatable, environment for US assets?

–

All that’s really happened in recent months is a return to realism: a reminder that the future is uncertain, and even long-standing trends can reverse in a heartbeat. Sentiment and valuations at the end of 2024 seemed to lose sight of these truths.

I have little idea what happens next. Maybe the US resumes its dominance. Maybe it enters a decade-long spell in the doldrums. Whatever the outcome, recent performance should prompt all investors to reassess risks that — if we’re being honest — many had stopped thinking about.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

New Decision Nerds Episode – Howard Marks

Even if we have a sound set of investment beliefs and a robust investment process, we will only be successful if we are able to stick with them through times of profound market uncertainty and anxiety. This is far easier said than done, as recent weeks have shown.

In order to get a better understanding of what it takes to be a disciplined investor over the long-term, who better to talk to than Howard Marks – Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of Oaktree Capital Management. He is, for my (and Warren Buffett’s) money, one of the most thoughtful and experienced investors of his generation.

Hopefully, you have all read his ever-excellent investment memos and, in the the latest episode of Decision Nerds, you can listen to our conversation with him in the midst of recent market upheaval. We had a fascinating chat – not about tariffs, Trump or trade wars – but the inner game; what investors need to make good decisions in difficult environments.

You can listen to the episode on your favourite podcast platform, or here.

What is Risk?

Investors talk a lot about risk, but nobody seems to be able to define exactly what it is. We like to use metrics and terms – such as volatility, drawdown and ‘permanent impairment of capital’ – to capture it but our reliance on such measures is more because they are observable rather than right. While we don’t need to precisely calculate risk, understanding it is essential to sound investment decision making. So, how should we think about it?

Perhaps Elroy Dimson put it best, and most succinctly, when he said: “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.”

This definition gets to the core of how investors should consider risk. Risk is an absence of certainty. Risky situations are defined by there being a range of potential future outcomes and some unknowable probability attached to those outcomes.

Imagine if I make a parachute from items I found around my house and then proceed to jump from the top of the tallest building in the world – this is an extremely high risk decision with the range of outcomes as wide as you could get (I live – unlikely, I die – probably).

Alternatively, if I decide to simply jump from the top of that same tall building (absent homemade parachute) that wouldn’t be a risky decision because the result is certain (or close enough to it). Choices are not risky because they are bad, but because the consequence of them is uncertain.*

When investors assess risk they should always be thinking about the range of potential outcomes stemming from a decision and their likelihood. I think most people instinctively think about risk in this way – certainly our behaviour often suggests we do – but we are rarely explicit about it. This is perhaps because it is harder to think about than commonly used risk metrics, and we do love to be able to measure things – even if those measurements are deeply flawed.

Risk in Action

To bring this idea to life a little, let’s consider two types of financial market environment and what happens to our perception of risk during them.

In times of extreme market stress, such as that witnessed in recent weeks, our feeling is that risk is increasing and we tend to behave in a risk averse manner. Why is this? Two things are happening. Firstly, our sense of the range of potential outcomes is widening. Secondly, we start ascribing higher probabilities to bad outcomes.

There are behavioural explanations for both of these phenomena. Our expectations for the future are heavily influenced by what has happened recently, so when markets are volatile in the near-term that fuels a sense that future outcomes are becoming inherently more uncertain. Furthermore, we tend to judge the probability of events based on how available they are to us – that is how easy it is for us to see and imagine something. In the midst of a market sell-off we will place an increasingly high likelihood on negative future outcomes.

Something close to a reverse of this situation occurs during bubbles. In spells of market exuberance our sense of the range of future outcomes narrows around high and unrealistic return outcomes, and we think the probability of such positive outcomes is increasing.

Bubbles are about performance chasing, social proof and storytelling, but they are also about a growing complacency around the real risk of an investment. In a bubble risk is growing but we act as if it is dissipating.

Time on our side?

Investor time horizons have a huge impact on risk. When individuals extol the virtues of long-term investing and suggest it is less risky than adopting a short-term approach, what do they mean?

If we are investing in equities for one year – what does the risk look like? The range of plausible outcomes is incredibly wide (+40% and -40% is not unreasonable for diversified index exposure); furthermore, the probability of negative returns is not immaterial. While, even over just one year, equity returns are more likely to be positive than negative that is far from guaranteed.

If, however, we adopt a longer term philosophy – let’s say 30 years – the range of potential outcomes narrows and the probability of positive outcomes is materially improved. In simple terms, I would be far more confident that equities will generate positive performance over thirty years than a single year.

There are good reasons for this. Over one year equity returns are driven largely by changes in sentiment, over 30 years it is the compound impact of earnings / reinvested earnings that will dominate.

When we are comparing the risk of investments across different time horizons, it is far easier to understand the concept if we ask the question – what does changing the time horizon do to the range of outcomes? And what does it do to the probability of those outcomes?

But, there is a catch. Extending our investment horizon does not always improve the odds of good outcomes. In fact, longer horizons can become the enemy.

A long-run horizon is generally a very good idea for most investors, unless we have an investment approach which carries a meaningful risk of disaster. If a strategy has the capacity for catastrophic or complete losses, long horizons work against us. If we are leveraged or concentrated then our risk increases as our horizon extends.

A three stock investment portfolio is a risky proposition with a very wide and uncertain range of outcomes. It is far riskier holding that portfolio for 10 years than one day.

Diversification and Risk

Although diversification is by no means a free lunch, it is an effective means of reducing and controlling risk, if done prudently. It works because by combining securities and assets with different future potential return paths it significantly constrains the range of outcomes of the combined portfolio.

If we move from a single stock holding to a diversified 50 stock portfolio we greatly lower the potential to make 10x our money, but also (nearly) entirely remove the risk of losing everything.

Diversification is a tool whereby we can (very imperfectly) create a portfolio with a range of potential outcomes that we are comfortable with. When individuals complain about over-diversification, what they typically mean is that the range of outcomes has been narrowed so that average outcomes are very likely. There is, however, no right or wrong level, it simply depends on our tolerance for risk. Or, to put it another way, our appetite for extremely good or extremely bad results.

The Stakes are High

When talking about risk as there being a range of future outcomes with some probabilities attached to them, I have missed out an important element – what are we putting at risk? What is at stake? A decision may be very high risk, but of little consequence.

If I bet one year’s salary on a horse race, that is a very different type of risk than placing a £10 bet. The risk inherent in the activity remains the same (the horse I have gambled on still has the same range of outcomes no matter how much I bet), but the risks to me are not comparable.

Risk is about understanding the range of outcomes and their potential probabilities, and then judging what the appropriate stake is given our view on this.

What is Good Risk Management?

I have tried to present what I think is the most realistic and sensible way for investors to think about risk, but what does that mean for good risk management? I think there are only three things that really matter:

– Understanding the potential range of outcomes and their probabilities.

– Reducing the probability of very bad outcomes (cutting the tail).

– Increasing the probability of good outcomes.

Of course, all of these things are difficult to do – but then that is the point. If the range of outcomes is incredibly wide then we need to know that – it will impact the choices we make. We will never know the range of outcomes or their true likelihood, but we can make reasonably educated guesses. We also know how to protect against the inherent uncertainty of the future (through diversification and time horizons) and how to avoid things that may cause catastrophic losses (such as concentration and leverage).

Risk management often goes wrong and it does so both behaviourally and technically. Behaviourally, because we have a plethora of biases – extrapolation, overconfidence, availability, recency etc – which mean we worry about the wrong things and are complacent about issues that should matter. Technically, because we try to precisely measure things where it is impossible to do so – inevitably becoming overly reliant on inherently limited metrics. If we use a single number to measure risk, we are not thinking about risk in the right way.

We don’t know much about the future, but we know more things can happen than will happen. We should invest with this in mind.

—-

* Risk and uncertainty are technically different things, but for most of us that distinction is not particularly useful.

–

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Bear Markets and Bad Decisions

Bear markets bring about increased risk but perhaps not in the way we might think. Sharp declines in equity markets create incredibly high levels of behavioural risk. The chances of us making decisions which compromise our long-run outcomes are incredibly high. There is no easy answer to coping with such spells – they are a challenge for us all – but there are some important things to remember:

Significant market declines always come with very bad news about the future:

It may seem obvious but is often ignored – large falls in equity markets come because of meaningful fears and uncertainty about the future. The specific cause of these will be different on each occasion. Markets don’t just drop, they drop for a reason and that reason will create profound worry.

This is why people who talk about waiting for ‘better prices’ to invest in equity markets probably never do – because those better prices arrive with bad news, news that makes us not want to invest. Everything will feel bad during a bear market, if it didn’t we wouldn’t be in one.

Risk is not a theoretical concept – it is about how we feel:

Living through a 30% decline in equity markets is an entirely different proposition to looking at a theoretical loss on paper. We might know that equities can fall a lot in the short-term, but we won’t truly understand what that means until we feel it. We are far more likely to insure our house against flood risk after it has flooded – risk often only becomes real when we have experienced it.

When we are living through market turbulence our appetite for risk will inevitably start to wane. Bear markets take a heavy emotional toll and can cause profound anxiety. Even well-adjusted and disciplined investors will be vulnerable because the longer and more pronounced the decline, the greater the chance that we start to question our own investment principles.

Reassessing our investment approach in a bear market is probably a bad idea:

It is often suggested that reviewing our investment approach during sharp equity market sell-offs is prudent. I understand the idea – confirming we are still comfortable with our plan amidst stressed environment seems sensible – but we need to be very careful here. It is incredibly unlikely that we will make good long-term decisions during times of acute worry.

When we are feeling anxiety, our body wants us to do something about it – this usually means removing its cause. That is why so many investors move to cash when equity markets fall – it relieves the pressure we are feeling in the moment, whether it is likely to come with a long-term cost will not seem like an important consideration at the time.

During bear markets the attraction of overhauling our investment approach and turning it into something that makes us feel comfortable right now will be incredibly strong, but making decisions about the future when under immediate pressure is rarely a good idea.

It is probably best not to plan next year’s holiday when we are on a plane suffering

from severe turbulence as we will probably end up choosing somewhere very close to home.

–

Our default assumption should be that decisions made during bear markets will be bad ones. Humans are designed to make certain types of choices under stress and few of these are aligned with good long-term investment thinking. This does not mean we should never do anything, but that we should exercise more caution than usual. The temptation to make choices that satisfy our current self at the expense of our future self will rarely be greater.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

A Guide to Navigating Tariff Turmoil

When equity markets are rising it is really easy to stick with the key principles required to be a successful long-term investor; unfortunately, it gets far harder when they start to fall and uncertainty climbs. At the exact time when discipline is required, it can so often desert us. The current tariff turmoil is a perfect opportunity to make some very bad decisions. To help avoid this, here are some dos and don’ts for investors:

– Don’t keep checking your portfolio.

– Don’t watch financial news.

– Don’t think you will make good investment decisions in this environment.

– Don’t make emotional choices – sleep on it.

– Don’t listen to people who didn’t predict the current market tumult, when they predict what is coming next.

– Don’t listen to anyone predicting anything.

– Do focus on your long-term investing goals.

– Do remind yourself that equity markets have generated strong long-term returns despite frequent periods of losses (which are sometimes severe and we cannot avoid).

– Do remember that equity market losses always come alongside some very worrying news about the future.

– Do remember that nobody knows what will happen next – it might get better, it might get worse.

– Do remember that this is why you hold a diversified portfolio and have a long-term time horizon.

– Do go for a nice walk in the fresh air.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

The Two Most Dangerous Words in Investing

For anyone interested in investor behaviour, extremes matter. When there is a severe dislocation between the value of an asset and its fundamental characteristics, or spells of dramatic price performance, it suggests that some of the most powerful aspects of group psychology are taking hold. Such situations create both significant risks and opportunities. The problem is that identifying extremes is much harder than it seems. There are, however, a couple of words than can help – ‘always’ and ‘never’.

Market extremes are obvious, but unfortunately only obvious after the event. Once the extreme has been extinguished, we can happily carry out a post-mortem on the irrationality that led to it, typically ignoring the fact that for the extreme to have existed many people must have considered it to be justified at the time.

And, of course, this has to be the case. For market extremes to be reached there has to be a belief that the levels of exuberance or dismay surrounding a particular asset class is simply a sensible response to a changing world. The performance and persuasive narratives that accompany financial market extremes are taken not as the cause of it, but as evidence for its validity.

This creates a problem for investors. Periods of extremes are critical and come with major behavioural risks, but we struggle to identify or acknowledge them in the moment. What can we do about it?

As usual, there is a heuristic that can help. Perhaps the most reliable indicator that sections of financial markets are exhibiting extremes in sentiment or valuation is when investors start to use the words ‘always’ and ‘never’. The more we hear these uttered, the more we should pay attention.

The problem with the words ‘always’ and ‘never’ in an investing context is that they suggest a certainty that simply does not exist in the complex and chaotic world of financial markets.

Whenever we fall into the trap of saying something ‘always’ or ‘never’ happens, we can be sure that a performance pattern has persisted for so long that we have become unable to see anything else in the future: The US will always outperform”, “yields will never rise” etc…

‘Always’ and ‘never’ are reflections of two ingrained and influential investor behaviours – extrapolation and overconfidence. Prolonged trends often become perceived as inevitabilities.

At the point we have decided that nothing different can occur, valuations have undoubtedly already adjusted to erroneously reflect a level of certainty in inherently uncertain things.

Thinking in terms of ‘always’ and ‘never’ has profound consequences for investors, particularly in terms of how we build portfolios. The more certain we are about the future and the more confident we are in the prospects for a particular security or asset class, the less-well diversified we will be. Portfolios built on the idea that things ‘always’ happen or will ‘never’ happen are probably carrying too much risk. Market extremes inescapably encourage dangerous levels of concentration and hubris.

Of course there are things in financial markets that we can be more sure of than others. Saying that technology stocks ‘always’ outperform is very different to claiming that equity markets ‘always’ produce positive returns over the long-run. Neither of these statements are true, but one is inherently more problematic than the other.

What investors really need to be wary of is situations where there is an evident gap between the level of certainty we can possibly have in how the future will unfold, and the certainty with which we talk about it. When that gap is wide it ‘always’ ends badly.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Improving Earnings Do Not Mean a Rising Stock Price is ‘Justified’

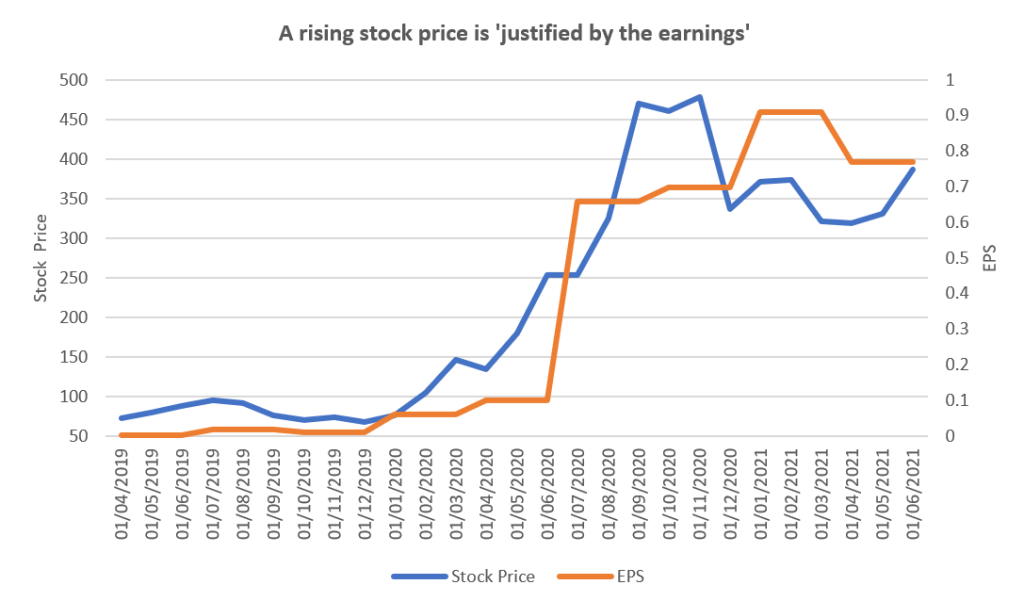

When a stock price has been enjoying a strong spell of performance it is increasingly common to see people argue that the move is ‘justified’ because earnings have been growing alongside it. The statement is usually accompanied by a chart a little something like this:

The point typically being made is that the company in question is not expensive because its increasing stock price is simply a reflection of improving fundamentals. This is a very simple and appealing notion, and also one which plays incredibly well visually. The problem is it can be exceptionally misleading as it ignores the critical variables that most long-term equity investors should care about.

Passing over the dual axis skulduggery which is so often apparent when these types of charts are presented, there are two major issues with making claims about the relationship between stock price performance and earnings growth:

1) Mixing the past with the future: EPS numbers are a reflection of the historic earnings of a company, while a stock price should (in theory) be based on expectations about the future earnings potential of a company. The only way that movements in EPS can ‘justify’ a current stock price is if it somehow affords us supreme confidence in the ongoing earnings prospects of that business. It may tell us a little, but it certainly does not give us a good answer to seemingly vital questions such as – how cyclical are the earnings of the business? What structural pressures might come to weigh on future profitability?

2) Ignoring valuations: The other glaring issue with such claims is that they seem to entirely ignore the valuation of the company in question. I appreciate that value has become a somewhat arcane topic but the earnings growth of a business surely has to be considered relative to its valuation. If we are attempting to assess the extent to which the EPS trajectory of a business is fairly reflected in its stock price movements, whether that business is valued on 5x earnings or 50x earnings feels like an important piece of information, but one which is often disregarded.

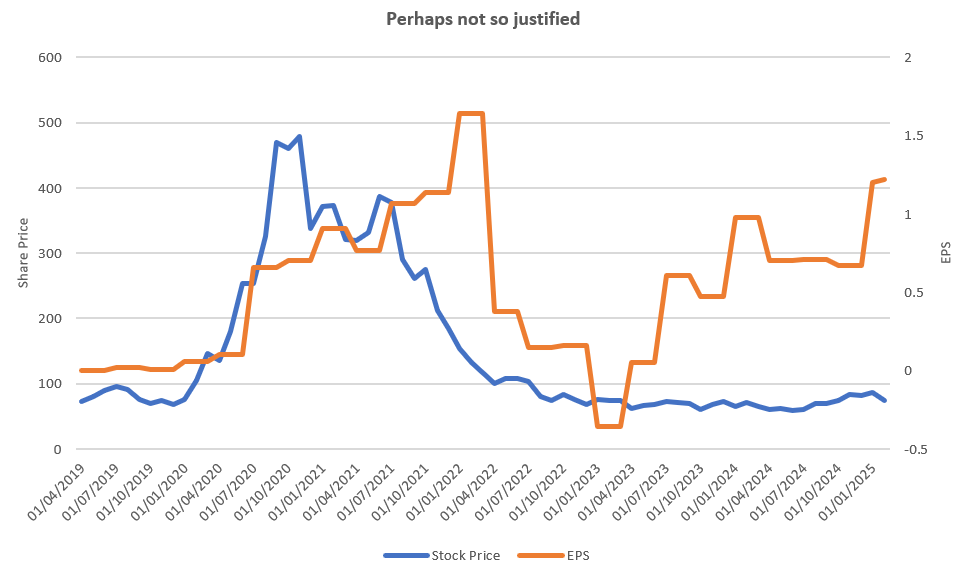

For a stock price to be fundamentally ‘justified’ in any way, we need to have a view on the valuation of a business relative to its future profitability. Observing a rising stock price and improving EPS really doesn’t help us answer such questions as much as many people seem to assume. Stock price moves can be justified by EPS moves, until they aren’t:

Although this type of comparison might not give us a great deal of information about the worth of a company, it does tell us a lot about the behaviour of investors and corporate management:

It’s all about earnings momentum: I have met many, many active equity investors in my career and I would say the most common approach is one based on earnings momentum; where the aim is to identify companies that are enjoying improving and consistently upgraded EPS. This is often not what is stated in their investment philosophy, but very apparent in their behaviour (there is a stigma attached to momentum investing and, unless you are a quant, nobody likes to admit they do it). The stock price to EPS chart is a simple representation of this type of momentum-driven activity.

This ubiquity of this type of investment approach is self-perpetuating. The more investors react to short-term earnings, the more stock prices react to short-term earnings and further encourage the behaviour. It is also a rational approach for many investors to adopt – if you have a time horizon of one or three years, then taking a momentum-orientated approach is likely the best survival strategy. Although you might care about the valuation of a business, by the time it starts to matter you may well be caring without a job.

Such momentum-led investors are as much, if not more, focused on how other investors will react to fundamental developments in the business, rather than the intrinsic merits of those developments to the business itself. There is nothing inherently wrong with such an approach, it is just different to being concerned about a company’s long-term value.

Corporate myopia: One of the consequences of the preponderance of momentum-orientated investors focused on short-term earnings developments is in executive behaviour. If positive stock price moves are increasingly the result of near-term EPS performance this will inevitably alter the decision making of management (on the assumption that their incentives are aligned with how the stock price performs). It seems reasonable to believe that there will be many occasions when a decision made with the objective of maximising short-term stock price performance is very different to one where the objective is long-term shareholder value maximisation. It would be nice if they were the same, but I seriously doubt they are.

The more short-term investors are, the more short-term management are. And so the cycle continues

The stock price of a company rising alongside its earnings really doesn’t help us understand whether it is justified or not, nor does it give us much indication about the long-term value of a business. Rather such comparisons tell us more about the type of investor we are.

* Charts comparing long-run equity market performance with earnings growth are fine. We should expect these to be closely related over time.

** To my mind, there are three types of active investors: Momentum, value and noise. Momentum investors care about price and are shorter-term. Value investors care about valuation and are longer term. Noise investors do random stuff and create opportunities for value and momentum investors.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

If Equity Markets Didn’t Fall as Much Their Returns Would be Lower

Perhaps it is the curse of frictionless trading and the rise of social media, or perhaps it is the unusually high returns delivered by global equities over the past decade, but investors seem more sensitive than ever to equity market declines. Even relatively minor ones like those experienced recently provoke dramatic responses.* At times such as these it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the returns from owning equities over the long run are as high as they are because they are volatile and suffer from intermittent drawdowns. We cannot have one without the other.

Starting with a very basic point – if we own a share of a company (hold equity), we carry the potential for a total loss of capital in the event that the business fails, and therefore we require adequate compensation for bearing that risk.

Thankfully, most investors are diversified across a large number of positions and are not entirely exposed to the fortunes of one company. We transfer the specific risk of part-ownership of a single business, to the broader market risk of holding a collection of them. This significantly reduces the range of outcomes we face – although we lose the potential for stratospheric returns from an individual holding, we also greatly diminish the prospect of disaster and complete failure.

This diversification benefit is an attractive trade-off for most investors, but although it limits one type of acute risk, it does not remove risk entirely. Even diversified equity exposure comes with risks and uncertainty that require compensation. This, however, is a feature not a bug – absent this uncertainty long-term returns would be significantly lower.

I tend to think about the risk to diversified equity investors as stemming from two types of uncertainty – short-term behavioural and long-term fundamental.

The short-term behavioural aspect is consistent with Thaler and Benartzi’s explanation of the ‘equity premium puzzle’. Investors are sharply sensitive to short-term losses and check their portfolios frequently. The daily fluctuations of equity prices create a huge amount of discomfort, which leads to poor behaviours, particularly during times of market or economic stress. The fact that this short-term volatility bears little relevance to the very long-term prospects of the asset class is largely irrelevant as – in the moment we experience it – it feels vital.

This creates a major advantage to investors with a long-term mindset (or the inability to check their portfolio valuations every day) but is far more difficult to capture in practice than in theory.

The long-term fundamental uncertainty element is simply that we cannot be sure what the results over time from equities will be. Although we can be confident that real returns from diversified exposure to equity markets will be positive if we hold them for twenty years – we don’t know whether this means 5% per year or 9%. Furthermore, we can never entirely discount the potential for very poor results from equities even over the long-run – the likelihood of this may be extremely low, but it is never zero.

These uncertainties combine to create high long run realised and expected returns for equities. If we were absolutely certain that equities would return 10% per year, then they would return a lot less than 10% per year.

There is a reward for bearing that uncertainty, but the catch is we do have to bear it. One of the biggest mistakes investors make is trying to capture the upside of equities while avoiding the downside. Given our dislike for even temporary losses this is entirely understandable, but incredibly dangerous, behaviour – one which is far more likely to act as a drag on performance than enhance it. The probability of us correctly anticipating and navigating each equity market drawdown (or prospect of one) is vanishingly small.

It is typically not the equity market declines that do long-term damage, it is the cost of the poor decisions we make during them. Such mistakes never come with just a one-off cost, they compound over time.

If we want to own equities for the long-term because we believe that they provide higher returns, it is important to understand why this is the case. Not only will this help us to manage the inevitably difficult times, but it will also allow us to shape our behaviour and time horizons to best capture those potentially high returns.

—

* Minor declines, so far. (18th March 2025)

–

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

New Decision Nerds Episode – Dealing with Trumpcertainty

Dealing with uncertainty is a constant challenge for investors, and now we are faced with a new and more dangerous variant – Trumpcertainty.

In the latest episode of Decision Nerds, we discuss the behavioural curse of uncertainty and how to cope in environments where it feels extreme.

We cover:

– Why uncertainty can feel worse than a loss.

– The evolutionary history of uncertainty aversion.

– How uncertainty impacts our behaviour.

– Why uncertainty acts as a decision making tax.

– How to communicate about uncertainty.

– What investors should and should not do in environments of heightened uncertainty.

The podcast is available in all of your favourite places, and here:

Dealing with Trumpcertainty