Evidence on the effectiveness of momentum investing is overwhelming – it has delivered a return premium across markets and asset classes, and there is over two centuries’ worth of data (see Asness et al. 2014). Whilst the performance advantage delivered is difficult to refute, it does present something of a puzzle – why should a strategy that is both technically simple to apply and behaviourally attractive deliver excess returns? Before exploring this question, it is worth clarifying these two claims:

Momentum is Easy: A standard time series, price momentum strategy is relatively easy to construct and operate. Although there are a vast range of iterations and nuances (this is the investment industry, after all) – the basic premise is to go long assets rising in value, and short those falling. The technical barriers to employing this strategy in some form are limited.

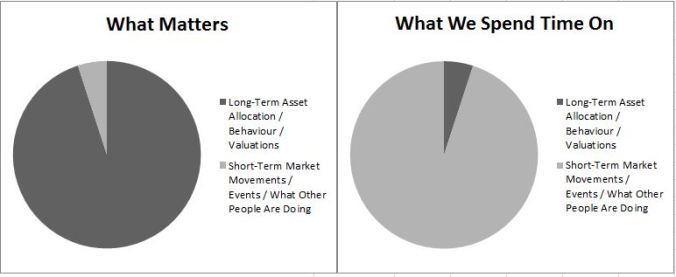

Momentum is Behaviourally Attractive: Most of us are wired to be momentum investors. Being part of the trend plays to our desire to be ‘right’, to be a member of the herd and to conform to the compelling narratives that price momentum inevitably generates. Participating in a momentum trade is psychologically comfortable.

Yet whilst most of us are momentum investors of some variety (often indirectly), rather than obtain the documented return premium – we help to create it. Our behavioural limitations mean that our attempts at discretionary momentum investing (driven by human decision making) are deeply flawed and incur a cost, which can be exploited by systematic approaches. It is important to remember that the evidence upon which the case for excess returns to momentum is built necessarily relates to systematic / rules based strategies.

In his book ‘Following the Trend’ Andreas Clenow described a traditional managed futures approach – a basic trend following strategy – as such:

“A statistical game with a slight tilt in your favour and that you just have to keep throwing the dice long enough to get the law of big numbers on your side”

This description bodes ill for the ability of humans to capture a momentum return. Victor Haghani and Richard Dewey produced a study where financially literate individuals (including some investment professionals) had to bet on the result of a coin flip, which was loaded in their favour 60/40. They started with $25, could bet stakes as small as $0.01 and were given 30 minutes. Despite this favourable setup, only 21% reached the maximum payout of $250 and 28% went bust. Even more curiously, 48% of players bet on tails (which had the 40% probability) more than 5 times. If our behaviour can be so irrational and erratic in such a dispassionate setting, it is no wonder that investors make consistently poor decisions in stimulating and emotion-laden financial markets.

To understand how momentum investing driven by human judgement serves to create a fecund environment for rules based momentum approaches, it is helpful to consider the central tenets of a typical systematic process and understand how this compares to the features of discretionary (or human) decisions:

| Momentum |

Systematic |

Discretionary |

| Winners Purchased |

Earlier |

Later |

| Winners Sold |

Later |

Earlier |

| Losers Sold |

Earlier |

Later |

| Diversification |

High |

Low |

| Rules |

Clear |

Vague |

| Persistence |

High |

Low |

The characteristic approach of a discretionary, ‘human’ investor described above is driven and shaped by a range of behavioural factors:

Buying Winners Late: Investors tend to underreact to news that fundamentally alters the value of a security. Whilst this phenomenon may be caused simply by the pace of information dissemination; it is more likely a result of commitment bias (our reticence to recant prior views) and also the gradual development of a new narrative – one piece of newsflow or data is unlikely to shift the prevailing market story, but if this persists the story surrounding it will build strength, drawing in investors. Also, as highlighted by Mark Granovetter (1978), we all have a different threshold for joining the riot (or herd) simply based on how many other people are participating. Momentum begets momentum.

Selling Winners Early: As detailed by Shefrin (2010), the disposition effect – the tendency to cut winners and run losers – has a material impact on asset prices and the momentum effect. In the case of relinquishing winning positions, investor willingness to sell on good news (and capture gains) serves to slow the adjustment of an asset price to its new fundamental value, thereby helping to foster momentum.

Selling Losers Late: Whilst arriving conspicuously late to the party, discretionary investors often overstay their welcome in loss making positions. Investors are committed to their viewpoint and suffer from confirmation bias, so may simply ignore new information that runs contrary to the view implicit in their positioning. This situation is exacerbated by cognitive dissonance, which makes them unwilling to crystallise losses and acknowledge error.

Lack of Diversification: Spreading risk across a variety of positions and asset classes is crucial to all sound investment approaches, but is particularly relevant (essential) for momentum-driven investing. The hit rate for individual positons can be low and predicting where momentum will arise (and be sustained) before the event is difficult. There is also the constant threat of sharp reversals, which can rapidly destroy gains made in previously successful positions. The danger for discretionary investors is that they become overconfident in their ability to identify the best trades and also overweight the most recent market activity. This can lead to exceptionally narrow portfolios focused on securities that have the strongest current momentum, rather than holding a diverse range of positions with varying levels of price strength. Whilst systematic momentum approaches can become concentrated, they consistently maintain a broad opportunity set and (should) have prudent risk controls.

Vague Rules: The best defence against the impulses of emotion or narrative-led decision making is a set of decision rules, which dictate investment behaviour. Systematic momentum approaches are founded on such principles, and actively divorce decision making from all intrusive elements except the key variable – which is typically price, but can include fundamentals, such as earnings. Discretionary human decisions are rarely driven by a binding set of rules and, absent strict guidelines, our actions are impacted by a range of factors, most of which have limited relevance to the judgement at hand. These might include: how we feel at the time of making a decision (our emotional state), our prior experience with a particular investment, the most recent news we have read, our belief in a particular narrative, or even how hungry we are (Danziger, Levav, & Avnaim-Pesso, 2011), and the weather (Hirshleifer & Shumway, 2003).

Being behaviourally consistent without a set of rules to adhere to is close to impossible; this was highlighted by Daniel Kahnemann (alongside Rosenfield, Gandhi and Blaser) in an article published in Harvard Business Review in 2016. The authors discussed how the influence of irrelevant factors can lead to huge variability in decision making; unlike biases, which tend to be consistent and persistent, the impact of noise is random and erratic – and therefore more difficult to mitigate. Even with the best intentions, the ability of a human decision maker to remain disciplined is severely limited.

Low Persistence: Perseverance is undoubtedly a key requirement for successfully capturing the momentum premium, and its return patterns make this an exacting challenge. The hit rate is unlikely to be high – therefore you will be ‘wrong’ frequently; furthermore, there will be many false dawns where momentum appears and rapidly evaporates. There will also be prolonged fallow periods in choppy markets where returns to momentum are poor, and short-term shifts in markets that see prevailing trends whipsaw and sharp losses incurred. Whilst a systematic, rules based strategy can be agnostic on such a performance profile (and indeed specifically designed to withstand it); the foibles of momentum are hugely problematic for discretionary investors, for whom it would be a herculean task to remain sufficiently controlled amidst the welter of behavioural impediments.

Whilst most of us are invariably attracted to momentum investing and carry it out in some form (even if it is merely implicit in our actions, rather than an express choice), few of us do it well. Our decision making is blighted by our behavioural shortcomings and the substantial influence of irrelevant ‘noise’. Human decision makers are willing but inferior momentum investors, creating the opportunity for systematic approaches to capture a premium.

—

Key reading:

Asness, C. S., Frazzini, A., Israel, R., & Moskowitz, T. J. (2014). Fact, fiction and momentum investing.

Clenow, A. F. (2012). Following the trend: diversified managed futures trading. John Wiley & Sons.

Danziger, S., Levav, J., & Avnaim-Pesso, L. (2011). Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(17), 6889-6892.

Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. American journal of sociology, 83(6), 1420-1443.

Haghani, V., & Dewey, R. (2016). Rational Decision-Making Under Uncertainty: Observed Betting Patterns on a Biased Coin.

Hirshleifer, D., & Shumway, T. (2003). Good day sunshine: Stock returns and the weather. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1009-1032.

Hurst, B., Ooi, Y. H., & Pedersen, L. H. (2017). A century of evidence on trend-following investing.

Kahneman, D., Rosenfield, A. M., Gandhi, L., & Blaser, T. (2016). Noise: How to overcome the high, hidden cost of inconsistent decision making. Harvard business review, 94(10), 38-46.

Shefrin, H. (2010). How the disposition effect and momentum impact investment professionals.