Although investing is far noisier and uncertain than most card games, it is also an activity where understanding the odds is critical. While investors may feel uncomfortable talking about their decision making in probabilistic terms, it is inherent in everything we do – whether we are explicit about it or not. Much like assessing our chances in a particular game of cards, active investors should be asking themselves three questions before making a decision:

1) What are the odds of the game?

2) Do I have skill?

3) What hand have I been dealt?

Let’s take each in turn:

What are the odds of the game?

This is simply judging the expected long run success rate of an activity – on the assumption that I am an average player. If my objective is to win at a game, I want to play the one where the odds are most in my favour.

For active investors this is about seeking to identify the structural inefficiencies in a market that might create advantages relative to an index tracking approach. Although these dynamics might change through time, they should move at a glacial pace.

To take a simple example of what this could mean – I might assume that the odds of success for an active equity fund manager are better investing in Chinese A shares than US large cap equities. This is because the former has more retail participation and may price new information less efficiently (amongst other things). This may not be true (there are certainly reasons why active investing could be harder in the Chinese domestic market), but such issues should be at the forefront of our thinking.

This is clearly not an easy judgement to make and there will be no precise answer, but it makes no sense to invest actively without first at least attempting to consider the odds of achieving a positive outcome.

Do I have skill?

The structural odds of a game are our starting point, but they will be impacted by the presence of skill. A poker player with evident skill should win more over time. The problem for investing is that skill is difficult to judge and far, far more people think they have it than actually do.

Skill can be quite an emotive term, so it is probably better to frame it as an edge. If I am going to engage in an investment activity with average or underwhelming odds, then I need to have an edge to justify participating.

Investors have terrible difficulty talking about skill and edge, but it is essential to do so. It might be analytical, informational, behavioural or something different entirely, but it must be something. If my choices are consistent with me believing I have an edge, I need to be clear about what I think it is.

What hand have I been dealt?

Sometimes the structural odds of a game, or the influence of my skill in playing it, can be dominated by whether I am dealt a great or terrible hand.

As an investor I can think of these as cyclical or transitory factors that influence my chances of outperformance. This is nothing to do with the perennial promises of it being a “stock pickers’ market” or other such empty prophecies, but rather factors like observable extremes in performance, valuation or market concentration that arise at different points through time and may have a material impact on my fortunes.

The best recent example of such a scenario would be in 2020 when a select group of high growth, actively managed equity funds had delivered staggering outperformance against the wider market. They had generated astronomical returns and held stocks that traded on eye watering valuations. Investing in such funds at this time (which investors unfortunately desperately wanted to do) is the same as being dealt a terrible hand in a game of cards. It overwhelms everything else – the overall odds of the game and our level of skill become irrelevant. The probability of achieving good outcomes from such starting points is inescapably low.

Of course, such a situation is even worse than being dealt a bad hand in a game of cards because investors – buying into the story and beguiled by past performance – will play it like it is a great hand.

The sad truth is investors are more likely to go ‘all in’ with an awful hand and fold a great one.

—-

Investors seem to dislike thinking in probabilities. In part this is because it can feel like we are applying spurious accuracy, but more because it can betray a profound uncertainty about the future, which jars with our general overconfidence. Despite this discomfort, we cannot escape the fact that we are playing a probabilistic game. We will never get to the right answer, but it would help our decision making greatly if we at least tried to carefully consider what our odds of success might be.

–

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Author: Joe Wiggins

Everything is Obvious

The dominance of US equities has been one of the most significant features of financial markets over the last decade. The sheer magnitude of outperformance makes it easy to claim that it has simply been a case of an in-vogue market enjoying a substantial and unsustainable valuation re-rating, but that’s not quite true. Although a material multiple expansion has been influential, fundamental factors – better growth and improving margins – have also been significant. There is a problem, however, with using these earnings advantages to justify the compelling relative returns produced by US equities. Implicit in these arguments is often the idea that it was obvious that this would happen, and now it is equally obvious that it will continue. This is where investors will likely come unstuck.

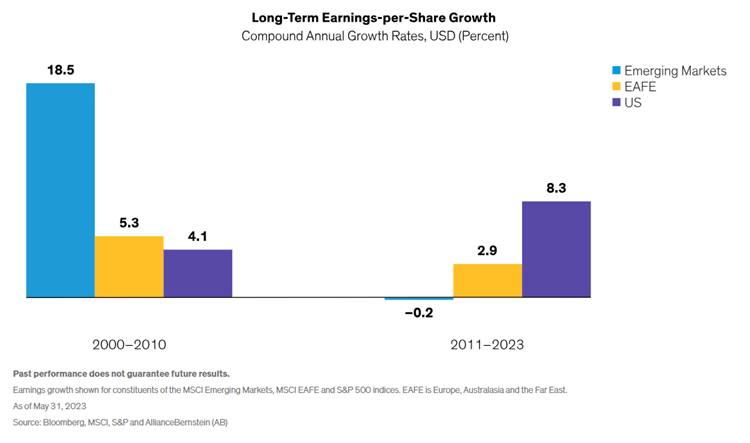

To explain why, we can look at this chart from Alliance Bernstein showing earnings growth across US, EAFE and Emerging Market equities:

How many people in 2010 were thinking – “over the next decade I believe US equities will be the place to be because of their earnings growth potential?” Not many. With the benefit of hindsight, we might think we were, but we weren’t.

Instead, we were likely to be saying: “Emerging market equity outperformance over the past decade wasn’t a bubble or about a valuation re-rating, it was about the fundamentals – haven’t you seen the earnings?”

In 2010, it would have felt obvious why emerging market equities had outperformed (‘it’s the fundamentals, stupid’) and that this would continue. It didn’t quite turn out that way.

These are the same arguments that are made now for US equities, but just applied to a different case at a different time. Our behaviours don’t change, just the subject that they are focused on.

There are two powerful and pervasive behavioural foibles at play here. Hindsight bias makes us feel as if the path we have taken was inevitable, whilst extrapolation leads us to assume that what has come before will continue. There is, however, something else that is just as problematic for investors – an inability to separate what matters from what is predictable.

Just because something will have a significant influence on the performance of an asset class, it does not follow that we can predict it with any level of confidence. Take earnings growth – this is a critical component of equity returns (the longer the horizon the more it matters) but is also incredibly hard to forecast. Just because something matters does not mean that it is a good idea to confidently forecast it.

Imagine attempting to estimate the relative earnings growth trajectories of emerging markets and the US back in 2010. That would require a wonderful ability to foresee developments in the growth of China, commodity prices and the rise of oligopolistic big tech firms (amongst a multitude of other things).

Added into this mix would have been the profound impact the strength of the US dollar has had on these fundamental fortunes. As currency forecasting ranks just below astrology in its accuracy, this makes life even harder. Earnings growth is really important, and it is also really important to understand our limitations in anticipating it.

When considering factors such as longer run earnings growth it is vital to accept that we are predisposed to be overconfident in our ability to forecast it and will also consistently assume that cyclical phenomena are structural. We should always start from a point of conservative assumptions based on long-run base rates and apply wide confidence intervals.

We must also remember that it should not be considered unusual for an outperfoming asset class to have had superior fundamentals. This is the critical part of the virtuous circle – better fundamentals – higher multiples – more persuasive stories. They feed on each other. The right question is not usually whether there has been any fundamental justification but whether it is sustainable and what is already in the price.

None of this is to say that the earnings advantage of the US will not persist. It is possible to make a perfectly plausible argument – probably around the rise of AI and the lack of effective antitrust enforcement – as to why this might be the case. It is, however, equally easy to contend that earnings are inherently cyclical and unusually strong tailwinds for certain markets (and industries within it) don’t tend to persist (they are unusual for a reason). This is without even considering starting valuations.

It is true that the outperformance of US equities over the past decade was heavily influenced by fundamental factors; it is not true that this was obvious before the fact, nor that it will necessarily persist. Anyone arguing otherwise is either wildly overconfident about their ability to see the future or trying to sell us something.

Things are never as obvious as they feel.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Forecasting is Hard and We Are Not Very Good At It. What Should Investors Do?

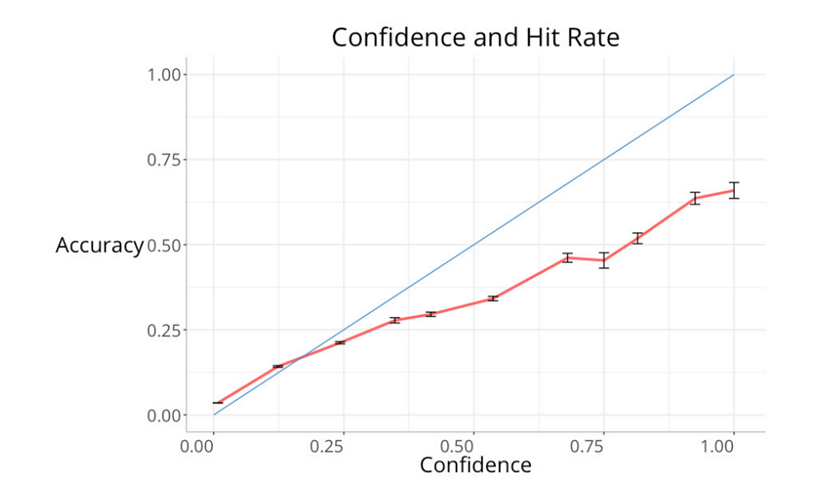

Although we might not like to admit it, we know that forecasting economic and market variables is tough, but just how tough? A new study by Don Moore and Sandy Campbell sought to answer this question.[i] They looked at 16,559 forecasts made in the Survey of Professional Forecasters since 1968, and found that those making expert predictions had 53% confidence in their accuracy but were only correct 23% of the time.

The study highlights the two central problems inherent in economic and market forecasting. It is not just that it is fiendishly difficult to get right (as the 23% shows), but we don’t appreciate how hard it is and are therefore poorly calibrated (the gap between 53% and 23%). This leads overconfident investors to make decisions based on unrealistic levels of precision.

One stark example in the study is that when forecasters held 100% confidence in their forecast, they were right only two-thirds of the time. Imagine the damage wrought by investment decisions based on an absolute confidence in the future. I am not even 100% sure the sun will rise tomorrow:

While the forecasters analysed in this study seem poorly calibrated, it is important to remember that they are doing things in the right way. They have expertise in their field, are adopting a probabilistic approach and receiving regular feedback on their quarterly forecasts. This is the correct method in making market predictions, yet overconfidence remains a major problem. Most investors making regular forecasts don’t have these attributes – we can only guess at the gulf that exists between their accuracy and confidence.

It gets worse still for investors. The study focuses primarily on single macro-economic variables – GDP, inflation and unemployment, but most investors are attempting to guess second order effects. How will ‘the market’ respond to changes in these factors. This adds another layer of unfathomable complexity to something that was challenging to start with.

Although the idea that forecasting is tough and people tend to be overconfident is hardly surprising, the results from studies such as these jar sharply with the everyday experience of financial markets, which are incessant stream of predictions. Investors are compelled to have a view on everything and must have conviction in that perspective.

But if we know that forecasting is incredibly difficult why can’t we stop ourselves from doing it?

Aside from simply thinking that we are better than other people, the primary reason is that predicting the future gives us comfort amidst profound uncertainty. It provides us a false sense of security in an environment that is incredibly chaotic. It is also expected of us – if everyone is making forecasts about everything then we should be too. Smart people are confidently foretelling the future – why aren’t we?

How can investors cope in a world where forecasting is endemic and expected, but very likely to lead to poor decisions?

Forecast the right things: Investors cannot simply stop making predictions. We all do it. Even the most ardent passive investing advocate is making implicit predictions about economic growth (economies will grow) and equity markets (equities will generate higher real returns than other asset classes) when building their portfolio. We should, however, be parsimonious in our predictions, modest in the assumptions required for our forecast to hold and have limited requirement for precision.

Focus on what matters: For most investors the list of things that actually matter to our long-run investment outcomes is far, far smaller than the things that we think will be of importance. To avoid getting caught up in the prediction machine, we should be clear about what these are from the outset.

Talk a lot, do a little: One of the reasons that forecasting is so prolific despite being so difficult is because investors always need something to talk about, and discussing financial markets can easily veer into forecasts about the future. It is okay to discuss about what’s happening in the world – in fact it might just be a requirement to keep people invested – but we should talk about markets far more than we do anything.

Understand we will be wrong, frequently: In the study, individuals with expertise, receiving feedback and taking a probabilistic approach were correct 23% of the time. We will be wrong far more than we think.

Prepare for a wider range of outcomes: It is not just that we will be incorrect, but the range of possible outcomes is likely to be wider than we will consider reasonable.

Be resilient to reality: We will be wrong more than we think and things will happen that are outside of our expectations, often by some margin. Our portfolio decisions and behaviour should reflect this.

Stop having views on everything: One of the most pernicious features of the investment industry is that everyone has to have a view on everything all of the time. Nobody can say – “I don’t know.” Given that forecasting is hard even for the best-prepared experts this is terribly damaging. We shouldn’t be asking why someone doesn’t have a view, but instead why they do.

Spend less time worrying about other people’s forecasts: Financial markets are populated by intelligent people making incredibly persuasive predictions. We should learn to ignore them. Rather than being captivated by a compelling view on the price of oil or the US dollar, we should instead be questioning why their ability to forecast is an exception to what the evidence so often tells us.

—

Nobody in financial markets will care that there is another piece of research highlighting quite how problematic forecasting can be, everything will continue as before. Investors who can, however, understand how hard it is and act accordingly will almost certainly be better off in the long-run.

[i] Overprecision in the Survey of Professional Forecasters | Collabra: Psychology | University of California Press (ucpress.edu)

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Having an Edge Isn’t Enough, Investors Also Need Patience

Imagine you are offered a bet on the outcome of the repeated flip of a coin. You can choose whether this is over 10, 100 or a 1,000 flips. Everyone thinks that a fair coin is being played, but you know that it is slightly weighted in favour of coming up heads. Which version of the game would you want to play? 1,000 flips, of course. If the probabilities are on your side then you want to extend the sample as much as possible – this gives the best chance of dampening the noise and letting the true odds come to pass. It is the same for investors – it is not enough to have an edge, you need to have the time for it to play out. That is a luxury that very few hold.

Blunting Edges

Unfortunately, life is a lot more difficult for investors than the coin flip example suggests. We never really know whether we have an edge (we just all think we do) and, if we are attempting to be a long-term investor, we may only make a handful of genuinely consequential decisions in our lifetime. The critical point is, however, if we believe that we have an investment approach where the probabilities are on our side then we have to give it time to work.

Having an investment strategy with an edge, and marrying that with a too short time horizon is identical to possessing no advantage at all. We are just entirely beholden to randomness. It is not enough for us to believe that the probabilities are in our favour, we must also be confident that we can persist with it so that we can benefit from those odds. If we cannot, then we shouldn’t be doing it.

For most investors, whether we have an edge or not is irrelevant because our time horizons (chosen or enforced) are too short for it to matter even if we did.

Disappointment and Disaster

If a good strategy benefits from a larger or longer sample then the opposite is also true. A bad investment process – one where the odds of success are against us – suffers from an extended horizon.

The worse our investment approach the more brevity is an advantage. We don’t want to wait to find the true odds, we want to be lucky.

If we have a sub-optimal strategy, the longer our horizon the more likely it is that we will encounter its disappointing reality. There is, however, something more pernicious than this slow trudge toward underwhelming returns, and that is an approach with the propensity for disastrous losses.

When there is the potential for catastrophe embedded within an investment process – most typically because they have leverage, concentration or both – time becomes our enemy. It is not just the odds that matter here, but the range of outcomes. Think of it like home insurance. If we decide not to renew our policy we make an immediate profit (or at least save on a cost), but expose ourselves to an incredibly unpleasant tail risk. A risk that increases with time. One day without insurance is a vastly different proposition to ten years.*

Asymmetric Agents

If an investment strategy has no edge, or carries the potential for severe and sharp losses, is it always better to have a shorter horizon? Not always. It depends on who actually bears the downside risk.

If there is a situation where an investor can benefit from the upside but other people suffer the losses then they will be incentivised to run even a poor strategy for as long as possible. The asymmetry is firmly on their side. They benefit from the luck and randomness that might result in positive outcomes, and are happily insulated from sharply deleterious outcomes.

This might seem like an unrealistic hypothetical but it is not. Imagine a hedge fund strategy capturing performance fees on an annual basis with no or partial claw back (not something that needs much imagination). They hold a free, or at least low cost, option on striking lucky, and they have no interest in that option expiring.

—

Investors spend a lot of time thinking about edges, but not a great deal of time thinking about what is required to benefit from them. For most it is not getting the odds on our side that is the difficult thing, it is playing the game long enough so that they matter.

–

* This relates to the importance of ergodicity in investment decision making – which you can read more about here.

–

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Has the Rise of Passive Funds Really Broken Markets?

Recent data from Morningstar showed that at the close of 2023, assets in passive funds had overtaken those in their active counterparts. This was a moment of celebration for advocates of passive investing, but also came against a backdrop of active investors – most notably hedge fund manager David Einhorn – claiming that this shift had broken markets. So, is the continued growth of passive funds simply validation for a better way of investing, or terrible news for the efficient functioning of capital markets?

Before getting into the details, it is worth emphasizing that the rise of passive funds has been an overwhelmingly positive development for investors. It is, however, possible to believe this and still ask valid questions about its implications. The move from active to passive investing changes behaviour – so it matters for markets.

I don’t have perfect answers to the questions that follow, but they are worthy of thought.

What proportion of assets are in passive funds?

It depends on what and who you ask. The Morningstar analysis did show assets in passive funds surpassing those in active funds, but the numbers shift depending on the region we look at, how passive is defined and what type of investors (mandates, funds etc…) are captured. One interesting aspect to consider, which is often ignored, is the proportion of active strategies (those trying to beat an index) that are heavily constrained in the amount of risk they can take away from their benchmark. They may have strict tracking error constraints or limits on the size of overweight and underweight positions they can take. Although they have more flexibility than a passive fund, the behaviour of the fund managers will be heavily influenced by the evolving composition of an index.

How many active investors do you need?

It’s difficult to say. Passive funds by their design benefit from the work of others. Active investors in aggregate set the prices of securities and then passive funds mirror this. This relationship only works if there are sufficient active investors engaged in some form of evaluation and analysis. If the market were entirely made up of passive investors prices would be set by flow and liquidity; fundamental business attributes would be largely irrelevant in market pricing (barring corporate activity around dividends, buybacks and issuance). In this scenario it would be fair to claim markets were broken in some way as passive fund behaviour would become entirely self-reinforcing and markets wouldn’t be useful in valuing businesses or providing some measure of the cost of capital.

Are all active investors trying to find ‘fair value’?

Absolutely not. Many critics of passive investing tend to create a binary distinction between passive investors being price insensitive and active investors assiduously building DCF models trying to value businesses. In my experience, this is simply not true. There are vast swathes of active investors that are far more interested in sentiment, momentum and price movements than attempting to work out something so arcane as what a company might actually be worth. The pervasive momentum and performance-chasing that we see in stock market returns is not a phenomenon caused by passive flows.

Are markets already priced by flows rather than fundamentals?

No. There is an argument that markets are already broken and dominated by price-incentive flows into passive funds, but this seems far-fetched. Let’s try a simple thought experiment – imagine that a major fraud was uncovered in one of the Magnificent 7 – would the price drop significantly because of concerns over future earnings or would the wall of money from passive funds overwhelm this? Almost certainly the answer is the former. The fluctuating fortunes of Meta in recent years seems a perfect example of market pricing still being driven (at least in part) by business fundamentals rather than flow. A far more egregious example of markets being driven by flows and sentiment was the Dot-com bubble, and that was fuelled by active investors.

Are passive investors value / fundamentals insensitive?

Yes and no. This seems like a simple one to answer but is a bit more complex than it first appears. If an investor is seeking to track the S&P 500 then they will buy irrespective of prevailing valuations, so in that sense they are insensitive to underlying business fundamentals and price. However, it is important to consider investors who are making active asset allocation decisions based on valuation and fundamentals but implementing them via passive funds. Many investors will appear valuation insensitive, but are simply considering these factors at an aggregate level rather than on an individual stock basis. (This relies on there being some active investors at a stock-level).

Passive funds just mirror current index weights, don’t they?

Not necessarily. The most compelling argument about the impact of increasing passive investment having a limited influence on markets is that that they simply invest at prevailing index weights – they perpetuate the current status quo rather than shift it. This argument only holds if we believe that liquidity and market cap scale equally, which they may not. If one listed company is 100 times larger than another is its relative liquidity 100 times greater? If not, then an increasing $ amount of money being invested in the largest index constituents may have some disproportionate impact on prices.

Is the growth of passive funds good for active investors?

Yes. Imagine you are an active investor and you are told that passive investing has broken markets so that stock prices bear little relation to fundamentals. This is great news! You are almost certain to find the opportunity to invest in companies that are wildly mispriced. You can invest at ridiculous prices and sit back and enjoy the fundamental returns of the business (just perhaps not a revaluation of the multiple).

Is the growth of passive funds good for active investors?

No. The above answer is only correct if you don’t require markets to ‘reprice’ the securities you hold. Inevitably one of the main groups criticising the rise of passive funds is hedge funds, one of the reasons for this (away from the general loss of business) is that they typically have short horizons (one year performance fees) and seek to capture anomalies / trends before other market participants. They make money when other investors play catch-up. In a world where passive flows dominate and there are fewer investors like them this process may take longer to occur.

Overall, the rise of passive investing should be great for increasing the opportunity set for active investors interested in mispriced fundamentals, but is problematic if you have short horizons.

Does the rise of the Magnificent 7 show that markets are broken?

No. While the Magnificent 7 may be expensive, their ascent has not been detached from fundamentals. In aggregate these are incredibly successful and profitable businesses. The stunning rise of Nvidia feels like a textbook case of improving fundamentals combining with a compelling theme and performance-hungry investors, rather than anything led by the increasing influence of passive funds. It doesn’t feel like anything we haven’t seen before.

Where is the impact of passive funds most likely to be felt?

Two obvious areas are non-index stocks and non-core markets. Stocks not featured in mainstream indices will almost certainly be impacted by the large increase in flow into passive products. This may well create opportunities, though this will be at the margins and will involve some lower quality businesses. There may also be some influence on non-core markets – for example, if the rise in passive investing increases relative flows into the S&P 500 this could impact the pricing and performance of smaller companies.

Is passive investing becoming riskier?

To an extent the more concentrated markets become the riskier a passive approach is. Let’s take things to an unlikely extreme – if the US became 90% of global equity markets with 50% concentration in the top 10 stocks and traded on 100x earnings, is a rigid passive approach still aligned with prudent investing? Probably not. But this is always a feature of passive investing not one that is caused by its growth. It is a known trade-off that passive investors must weigh up against the advantages. (Passive investors would have been buying a lot of Japanese equities at the peak of their bubble).

Does the rise of passive funds change investor time horizons?

Yes. It is reasonable to believe that increasing flows into passive fund requires fundamentally driven, active investors to increase their time horizons because on balance it may take longer for those fundamental factors to come to pass – at a security level there are fewer valuation sensitive buyers and greater weight of money invested at index weights. This creates something of a dichotomy because the rise of passive funds has inevitably shortened investors’ horizons – the tolerance for underperformance in active funds has likely reduced because the switch to passive is so easy.

The edge available to active investors with a long-time horizon is probably increasing, but the ability to adopt such a horizon is reducing.

–

It is hard to disassociate valid questions about the implications of the rise in passive investing from gripes by individuals and groups who have been disadvantaged by its growth. The market has evolved, however, and it would be remiss not to consider what that may and may not mean. On balance much of the market activity that is used as evidence of the pernicious impact of passive investing feels like behaviour we have experienced in the past, long before passives played such an influential role. That is not to say there has been no impact, nor that it is a phenomenon to disregard, but, as it stands, my best guess is that the rise of passive may make trends run a little harder and reversals more severe, but it is difficult to argue that markets are broken.

—

Links

Morningstar: Passive Overtakes Active

Masters in Business – David Einhorn Interview

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

New Decision Nerds Episode – The Other F Word

Thinking and talking about failure can be tough, especially if it’s us who’s got something wrong.

But it’s vitally important for us as individuals and teams to find a way to address failure that allows us to both learn and evolve. In this episode of Decisions Nerds we:

– Examine my framework for thinking about errors around investment beliefs, processes and outcomes.

– Think about this in the context of broader typologies of errors; basic, complex and intelligent.

– Discuss some of the key psychological factors around failure and how they can be managed.

Some key takeaways:

The world of investing is filled with uncertainty and many of our decisions are going to be wrong.

We tend to look away from errors because of confusion about what caused them and fear of repercussions.

We can make life easier for ourselves when:

1. We accept failure and build processes that make us examine it.

2. We develop clear typologies of failure that are rooted in the decisions our teams make.

3. We build cultures of strong psychological safety.

As a bonus, you can hear me enjoy some live tech failures to bring the episode to life.

Play below, or find in all your favourite pod places.

https://decisionnerds.buzzsprout.com/2164153/14540844

Election Years are Dangerous for Investors (Just Not for the Reasons We Think)

It will not have escaped anyone’s attention that 2024 is a significant political year. Over 50 countries – home to somewhere near half of the world’s population – will hold elections. This – in particular the US presidential vote – is currently exercising financial markets. There is much talk of rising uncertainty* and a frenzy of predictions about results and their consequences. Given this backdrop, investors have every right to be worried, but perhaps not for the expected reasons. We should be focusing less on the specifics of the elections and more on avoiding the poor decisions we are likely to make because of them.

A US election is fertile ground for market forecasters. They can speculate both about the result of a significant occurrence and the market’s response to it. The prognostications typically involve either predicting the short-term reaction of market participants (how other people doing the same thing as them will act), or specifying some longer-term structural shifts that might occur as a consequence (what happens to the US dollar? Which industries stand to benefit?)

Should we act based on either of these types of predictions? Our strong default should be no. These are highly unpredictable, impossibly complex and chaotic subjects that we are understandably not very good at judging. Will some market soothsayers be right? Probably. Do we have any idea who will have that honour this time around? Probably not.

It is not just that it is incredibly difficult to make forecasts or to know whose forecasts to follow, but for most investors the thing we are anxious about will matter much less in meeting our specific goals than we think.

The challenge is that the industry compels action – it generates far more heat than light. It wants us to trade, to switch funds and to pay for critical insights. Even investors who really don’t want to engage with these issues are forced to simply because everyone else is – otherwise we risk seeming negligent.

There are two critical questions to consider when ‘significant’ market events are looming, or we are tempted to trade because of some noteworthy development:

1) Is it important to achieving our goals? Generally, events are far less critical to investors and our long-run returns than we perceive them to be.

2) Can we predict the event and the market’s reaction to it? Almost always the answer to this question is no.

It remains fascinating how investors face an incessant bombardment of evidence about how bad we are at making predictions and timing markets, yet we continue to persist with a punishing indefatigability. We were wrong yesterday but will be right today.

Major events – such as elections – are particularly pernicious because their prominence means that the urge to act can prove irresistible. As humans we are wired to deal with what is right in front us. The more salient and available an issue, the more we are likely to act. Far better to do something destructive than to be a bystander.

As difficult as it is, as investors we would be well-placed to reframe our approach. Rather than respond to each major event or period of ‘increased uncertainty’, we should instead try to move our focus to managing behavioural risk. That is identifying environments where we are likely to make poor investment decisions that damage our long-term returns, such scenarios might be:

– Significant market / macro events (elections / recessions / wars)

– Periods of extreme performance (bubbles and busts)

– Paradigm shifts (the next new transformative market narrative)

In these environments – where the behavioural risk gauge is flashing red – it will be the poor decisions we make because events are happening, rather than the events themselves, that will be of greater consequence.

—

* I am always slightly sceptical of the warnings of rising market uncertainty. Both because markets are always uncertain but more because it suggests that we were more certain about markets before they became uncertain (which means we were wrong to be more certain in the first place!)

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

Which Type of Investor Are You?

It is so tempting to get lost in the noise and intrigue of financial markets that we can easily forget what type of investor we are. Although the investing community can at times appear something of an amorphous blob attached to the latest in-vogue topic; groups of participants are engaged in wildly different activities that – at anything but a cursory level – are barely related. To have any chance of success it is critical to understand the realities of our own approach and avoid playing somebody else’s game.

In broad terms, I think there are four investor types:

Trader

A trader operates with ultra-short time horizons (intra-day to weeks) and is typically engaged in the prediction of price movements based on historic patterns or the expected market reactions to certain events (if X happens, prices will do Y). Asset class valuations and fundamentals are largely irrelevant, and the focus is on forecasting the response function of other investors.

This is staggeringly difficult to do consistently well, which is why profits often seem to accrue to the people who teach trading to others rather than do it themselves.

Price-Based Investor

Almost certainly the most common active investment approach. Price-based investors have short time horizons (ranging from three months to perhaps three years) and tend to engage in one of two related activities:

1) Predicting future market / macro factors and how other investors will respond to them. “We believe that the Fed will be more accommodative than the market expects, which will support US equities.”

or

2) Predicting how other investors will react to realised market / macro factors. “The Fed is far more dovish than the market expected, therefore we have increased our exposure to US equities.”

The common factor in both of these closely related methods is that investors are guessing how other investors will behave. This is similar to trading, but the horizons are extended (though still what I would class as short-term). In essence it is an attempt to capture anticipated price trends.

Valuations and fundamentals matter somewhat for this group, but only insofar as they are useful for understanding the positioning and future decisions of other people like them.

This is probably the most comfortable style of investing from a behavioural perspective as it caters to plenty of our biases – our desire to be active, to be part of the herd, to tell stories. For similar reasons, it is also likely to prove the most prudent survival strategy for professional investors.

The problem is that it is incredibly challenging to get these types of calls right (or even more right than not).

Valuation-Based Investor

This type of investor is focused on the fundamental attributes of an asset and will look to make some assessment of expected return or fair value based on analysis of starting price and future cash flows. Given that price fluctuations dominate short-term asset class performance, a long view is essential.

It is important not to confuse a valuation-based approach with value investing, which is only a subset of it. Valuation-based investors are seeking to identify asset mispricings – these might occur because the level of growth is underappreciated, or high returns on capital will persist. The key distinction is that the focus is on the returns produced by the asset rather than how other investors might trade it.

Given that market movements over short and medium horizons often bear little relationship with the fundamental features of an asset class, a valuation-led approach is undoubtedly the most behaviourally taxing. This group will inevitably spend a great deal of time appearing out of touch and idiotic, even if they are right, and they might end up waiting years for validation that never arrives (taking a valuation-led approach doesn’t mean that you will necessarily be correct in the end).

Relative to a price-based investor they are more likely to be successful in their investment decision making, but also more likely to lose their job.

Passive Investor

Although there is no purely passive portfolio, this group seeks to invest in a fashion that can be considered a broadly neutral representation of the relevant asset class opportunity set (by size). While passive investors are inherently agnostic on valuation, they do care about the fundamental features of the assets in which they invest, but specifically in regard to the ultra-long run, or structural, expected risk and return.

A passive investor may not believe that markets are efficiently priced, but simply there is no reasonable and consistent way of capturing any inefficiencies (certainly relative to the effort or behavioural stress required), particularly after costs.

Although a long-term, passive approach appears simple it is not without behavioural challenges – doing nothing is tough and rarely lucrative. There will also be incessant speculation around how some profound change in asset class behaviour will soon render a passive approach defunct.

But perhaps a more credible problem is that a purely passive style requires investors to be ambivalent about extreme asset class overvaluation – passive investors are fully / increasingly exposed to equities trading at 100x PE or bonds yielding zero – even if the evidence suggests this will lead to derisory future returns. It is reasonable to suggest that this is a known cost and one which still leaves it superior to other strategies. It should not, however, be ignored.

—

These categories are not quite as discrete as I have made out, but the overall point holds. Defining our own approach and understanding its realities and limitations is absolutely critical for any investor. This requires setting realistic expectations, knowing the information that matters and what should be ignored, and preparing for the specific behavioural issues we will encounter. Failure to do this will mean we will inevitably become part of that amorphous blob.

All investors should be asking who they are and what it means.

–

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

The Three Types of Investing Mistake

It doesn’t matter whether we are an experienced or novice investor, we will all face plenty of situations where our decisions go awry and investments fail to meet our expectations or goals. It is easy to say that we should all spend more time thinking about and learning from our errors, but it is not quite that simple. Although it might seem obvious, it is not always clear what an investing mistake is. Are poor short-term returns from a long-term position a fault or meaningless noise? What about underperformance from holdings in a diversified portfolio that would have fared well in a different future? Misdiagnosing what a mistake is may well be as damaging as simply being ignorant to them. To avoid this, it is helpful to think about investment mistakes in three ways – those related to beliefs, processes and outcomes:

Belief Mistakes

Almost certainly the most commonplace, but least appreciated, cause of investing disappointment are mistakes of belief. This is where our foundational belief or philosophy is flawed.

Let’s take an example. We adopt an investment approach that is designed to tactically allocate across asset classes based on a three-month view. After a period of implementing this strategy, it is very likely that our performance will have been underwhelming. Our instinct will be to try to remedy the situation by adjusting the process – refining the inputs and our implementation – but the process isn’t the issue, rather it is the idea that asset class performance is predictable over such short horizons. If our beliefs are wrong from the outset, adjusting the process is not going to provide a solution.

Mistakes of belief occur when we incorrectly believe that what we are trying to achieve is reasonable and feasible. This leads to us engage in investment activities where the probability of success is extremely low. Why do we do this? The obvious answers are overconfidence and perverse incentives. We either hugely overstate our ability to succeed in an activity, or we are paid for it, so we do it even if we realise that it is not a good idea.

The real challenge of erroneous beliefs is that they are so difficult to change. When we alter our investment process it can be regarded as a welcome evolution or refinement – we are taking a positive step to get better. When we change our investment beliefs we risk tarnishing our reputation and identity (which is why it so rarely happens).

Process Mistakes

Even if our investment beliefs are credible and sound we can still err. A process mistake is where there is some flaw in the way in which we implement our beliefs.

The typical cause of bad outcomes from a mistake of process is technical. Here there is a weakness in our analysis of the information or use of it. What we believe is true, we just have failed to implement it well.

It may be perfectly reasonable to believe that we can lose 10lbs over the next 6 months, but if we have no idea how to design a sensible diet and exercise strategy, we are probably not going to achieve it. There is a belief and process gap.

The other type of process mistake is behavioural. This is about our ability to enact and maintain a plan. This is a serious problem for investors. We can have a sound set of foundational beliefs and a robust process but fail because we have underestimated our own behavioural limitations. This is not just an issue for individuals, but also for institutions who spend a great deal of time refining processes but seemingly little on whether the decision-making environment is supportive of the desired approach.

We have the perfect plan for losing 10lbs, but have entirely ignored the behavioural challenge of going to the gym or not eating that cake.

Outcome Mistakes

One of the toughest parts of being an investor is that there is no clean and consistent link between our beliefs and processes, and the outcomes we receive. We can make smart, evidence-based decisions and end up looking clueless; or appear to be a genius from making an ill-educated punt. Financial markets are fickle and unpredictable; talented investors will experience plenty of bad luck and see lots of things that look like mistakes but really aren’t.

The key danger of outcome mistakes is that they can lead us to give up on an investment strategy that works because we either misinterpret the results or struggle to accept the reality that good long-term investing comes with plenty of pain. There are four types of outcome mistake where we do the right things, but get the wrong results:

1) Bad luck: We simply suffer from misfortune. The more chaotic and unstable an environment, the more things can transpire against us.

2) Goal mismatch: A frequent issue for investors is where we compare our results against something that we were not even targeting. The most common example is worrying about short-term performance when we have long-tern objectives. This is akin to running a marathon and judging our success after the first mile.

3) Cost of sensible diversification: Well-judged diversification means being positioned for a range of different outcomes, not trying to maximise returns based on a single vision of the future. Being diversified requires holding positions that look like mistakes.

4) Natural failure rate: Even if we have solid beliefs and an incredible process it is likely to have an element of failure built into it. If we can score 90% of our penalty kicks or covert 75% of our 50+ yard field goals then we are delivering exceptional results punctuated with the occasional failure. The more difficult an activity, the more good operators have to accept mistakes, and, crucially, avoid overhauling their approach when they occur.

—

If there is randomness and uncertainty in an endeavour, identifying and dealing with mistakes will always be difficult. For investors, a perceived failure could be the result of a profound flaw in our thinking or simply an inevitable feature of a sensible investment approach. So, what can we do about it?

We should begin by defining what it is we believe and setting reasonable expectations; these are the foundations of any investing approach and without them we really don’t have much of a hope. With these in-place we must make sure we record and review our decision making through time. This means detailing and maintaining a clear rationale for our choices at the point at which we make them; and crucially avoiding the trap of judging past decisions through the horribly biased lens of hindsight.

It is easy to believe that investors are prone to ignore thinking about their mistakes because it is too psychologically painful, while this notion certainly has merit the truth is far more complicated. Our starting point shouldn’t be trying to identify our own mistakes, but defining what mistakes actually are.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).

My Top Stock and Fund Picks for 2024

I have brought you to this post under false pretences because I don’t have any fund or stock picks for the year ahead; but if you have read this blog before you may have already guessed that. Recommendations for individual stocks and funds are a persistent feature of the investment landscape, but are particularly prevalent at the start of the year. Unfortunately, these are a terrible idea for investors and encourage the most harmful behaviours. They should be added to the ever-increasing list of ‘stuff to ignore’.

The recommendation of specific stocks is the most egregious practice. Any single stock is a highly risky investment and has a huge range of potential outcomes; most investors do not need to be dabbling in such areas. It is also incredibly difficult to do well – even for dedicated, experienced professionals. We know that the success rate of most active equity fund managers is low and that those that are successful rarely get many more than 50% of their decisions right – why would it ever be a good idea to think that focusing on one or two companies would be prudent?

Advocating certain funds is somewhat less heinous than stocks because of the inherent diversification and ongoing stewardship, but still entirely unnecessary. Often recommendations are for flavour of the month areas, or in niche, high risk segments of the market offering the false allure of stratospheric returns.

Even if the individual suggesting the stock or fund ideas has some skill (which is impossible to know) the time horizons involved renders this irrelevant. Over a 12-month period nobody knows which stocks or funds will outperform, the amount of noise and randomness involved is overwhelming. But that doesn’t matter because next year there will be a fresh set of recommendations and the current ones will be a dim and distant memory (apart from those that have done well, which may just get a mention).

This type of endorsement leaves investors incredibly exposed. What happens if we follow a stock or fund pick and two months down the line there is a negative development? What do we do if the stock has an earnings disappointment, or a fund manager departs? There is often no recourse or requirement to update the view – we are on our own from the moment the proposal is made.

There is also no accountability. We have no meaningful way of knowing whether the person making the suggestions has expertise (not that it really matters), nor do they have any skin in the game regarding the consequences of the choices that are made.

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of such stock and fund picks is that they are typically devoid of context. What is the situation and disposition of the individual reading the article? How might this recommendation fit within a wider portfolio? Do they understand the risks involved? Individual fund and stock picks are a bad idea for us all but can be terrible for some.

These recommendations often do little more than perpetuate a dangerous short-term mindset – offering persuasive and captivating ways of making more money and making it quickly. In truth, investors should not be focusing on any individual stock or fund, nor believe that anybody has a clue about what will perform well over the next year.

Such guidance is good for commissions and clicks, but bad for investors.

—

My first book has been published. The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions. You can get a copy here (UK) or here (US).